Changing the Nostril Shape

Anthony E. Brissett, MD, and David A. Sherris, MD

The nasal base and nostril shape are important characteristics to consider during the planning and execution of aesthetic and reconstructive rhinoplasties. The first descriptions of nasal base reductions to alter the nostril shape were described more than a century ago by Weir. Modifications of this technique were reported by Joseph." In 1943, Aufricht, using the methods of Weir and Joseph, described a modified technique in alar reduction that remains popular today.' The authors present a discussion on anatomic aspects of the nasal base, strategies to analyze the nasal tip and nostril shape from the base view, and variations in nostril shape. Finally, a systematic approach of surgical techniques to alter the nostril shape is provided.

ANATOMY

In evaluating the nostril shape from the base view it becomes apparent that contributions from the lower lateral cartilages, the anterior nasal spine, the caudal septum, the maxilla, the upper lip, and the skin and soft tissue envelope of the nose all contribute to the overall appearance. Variations or changes in any of these structural components or their relation-ships to one another may alter the appearance and attractiveness of the nostril shape, and ultimately, affect nasal function.

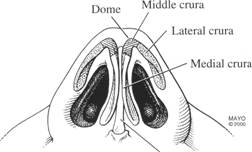

The lower lateral cartilages (LLCs) are critical in defining the nasal tip and nostril shape. Each LLC is composed of three crura: the medial, middle, and lateral (Fig. 1). Each of these portions is composed of two segments. The medial crus is divided into the footplate and columellar segments. Angulation of the foot-plate segment occurs in a medial to lateral and anterior to posterior direction. The columellar segment is ideally oriented vertically and is primarily responsible for nostril length and nasal tip projection.

The middle crus begins at the columellar and lobular juncture and ends at the lateral crus.'" Its two components are the lobule and domal segments. The lobular segments can be extremely varied, and this corresponds to much of the extensive variation and diversity in tip shape. One of the hallmark features of the domal segment that affect appearance of the nasal tip and nostril shape is notching of the cartilage at its caudal aspect. This notching corresponds to the soft tissue triangle of the lobule. The lateral crus is the primary component of the nasal ala. It begins at the nasal domal junction and courses laterally and cephalad. The lateral crus terminates in a chain of accessory cartilages.

EVALUATION

|

|

With this in mind, it is important to recognize that significant individual and racial and ethnic variations within the structural components of the nasal tip exist. These anatomic variants correspond to dramatic differences in nasal tip size, shape, and nostril configuration. In general, the nose can be described as being platyrrhine (African), mesorrhine (Asian), or leptorrhine (Caucasian) (Fig. 2).10 The African and Asian nose, to varying degrees, share many common features and can be described as less projected and having a shorter columella, increased nasal flare, increased interalar width, and more horizontally oriented nostrils when compared with the leptorrhine nose. A poorly defined anterior nasal spine, decreased vertical projection of the columellar segment, thinner and less rigid lower lateral cartilages, and thicker skin with increased subcutaneous

fat are some of the structural differences that account for the variance.

The axis of the ala is critical for surgical planning. Sheen16 defined three varying alar axis: divergent, straight, and convergent (Fig. 3). Alar base reduction should be discouraged in patients with a convergent axis.' When evaluating the nasal tip from the base view, it can be divided into seven subunits (Fig. 4). The various subunits correspond to the segments of the lower lateral cartilages discussed previously. In addition, nasal width, tip projection, nostril shape, and symmetry are evaluated best from the base view.

When deciding on which base reduction techniques will produce the desired outcome, the rhinoplastic surgeon must distinguish between alar flare and alar base width.' Alar flare is the maximum degree of convex bowing of the alar base above the alar crease. On the other hand, interalar width or alar base width is the distance from one alar crease to the other (Fig. 5A). Alar flare and increased alar width can be responsible for increased nasal width. Specific strategies to address these abnormalities are discussed in the section on operative techniques. When evaluating the nasal tip from the frontal view, the width of the nose should not extend past the imaginary line that extends inferiorly from the medial canthus (Fig. 5B).

Tip projection as seen from the base view can be analyzed best by using ratios and proportions. In general, the nostril width, from alar crease to alar crease, should be equal to the nostril height measured from the subnasale to the nasal tip defining point. The nostril to infralobule ratio should be approximately 2: 1. Farkas et al described seven standard nostril types varying from vertical to horizontal in orientation (Fig. 6). Round and horizontal nostrils are often associated with poor projection. The ideal nostril shape is elliptical, with its axis at a 45° angle measured from the lateral border.'

Figure 2. Variations in nasal shape based on race. The leptorrhine nose (A, Caucasian), when compared with the platyrrhine nose (C, African), has increased tip projection and more vertically oriented nostrils. The mesorrhine nose (B, Asian) has intermediate features. Nostril to infralobule ratios decrease when progressing from leptorrhine to platyrrhine. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 3. The alar axis as described by Sheen. A, Divergent. B, Straight. C, Convergent. (From Sheen JH: Adjunctive techniques. In Sheen JH, Sheen AP (eds): Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. St. Louis . Mosby, 1987; with permission.) (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 4. Seven subunits of the nasal base. (1) Columella base, (2) central columella, (3) infralobular triangle, (4) soft tissue triangle, (5) lateral wall, (6) ala, and (7) nostril sill. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 5. A, Alar flare, described as the maximum degree of convex bowing above the alar crease. Alar base width, the distance from one alar crease to the other. B, Optimal nasal tip width from frontal view is equal to intercanthal distance. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

When deciding the appropriate surgical procedure to use for tip refinement and nostril shape augmentation, the structures that are responsible for creating a misshapen nasal tip and nostril must be considered. A systematic approach to the various subunits is described. For illustration purposes, the procedures are described as isolated or individual techniques. Multiple procedures, however, may need to be performed simultaneously to obtain the de-sired appearance and achieve a satisfactory aesthetic and functional outcome. In the rhinoplasty operation, aesthetics and function set the objective and anatomy determines the operative technique.'

Nasal Base

Changes to the nasal base require addressing the alar base and nostril sill. The most dramatic deformity of this area is the cleft lip nose. The severity of the nasal deformity is proportional to the severity of the cleft lip deformity. The anatomic characteristics of the unilateral cleft lip-nasal deformity have been well described. Multiple procedures using closed and open rhinoplasty techniques are described throughout the literature. By closing the cleft lip deformity with the Millard technique, satisfactory correction of the lip and nasal deformity is sometimes possible primarily (Fig. 7). A common finding with the bilateral cleft lip nose is underprojection and a short columella. Using a V-Y advancement technique incision allows the surgeon to ex-pose and augment the nasal tip structures while lengthening the columella'' (Fig. 8). Discrepancies of the alar base or the nostril sill correspond to asymmetric nostril shape. In addition, alar flare and increased interalar width lend themselves nicely to alar base reduction techniques. There are multiple variations of alar base excisions that are, in some form, a modification of the techniques initially de-scribed by Weir, Joseph, or Aufricht (Figs. 9A and C). If the problem is isolated to increased alar width, direct excisions of the nasal sill should be performed (Fig. 9B).

Figure 6. Nostril types as described by Farkas et al. (From LG, Hreczko TA, Deutsch CK: Objective assessment of standard nostril types: A morphometric study. Ann Plast Surg 11:381-389, 1983; with permission.)

Figure 7. A, Unilateral incomplete cleft lip deformity with concomitant nasal deformity. B, Postoperative cleft lip re-pair using Millard technique. Note improvement in nasal deformity.

If a large amount of tissue excision is required for adequate reduction of interalar width, an alternative to direct nasal sill excisions is the alar cinch' (Fig. 10). This technique requires releasing and repositioning of the ala at its base. It becomes apparent that narrowing the alar width results in modest increases in tip projection and reorientation of the nostril to a more vertical configuration. An additional technique that can be used for addressing nostril asymmetry, alar flare, and increased interalar width, is the alar base stitch. This procedure can be performed as a unilateral or bilateral procedure with corresponding effects to projection and nostril orientation (Fig. 11).

Reconstruction of the nasal tip often re-quires the transfer of tissue from local and regional sites. The differences in skin thickness brought in to reconstruct the defect may result in excess tissue bulk and narrowing of the nostril. Inferior based transposition flaps work well to correct this type of deformity of the nasal base (Fig. 12).3 On occasion, discrepancies of alar flare can also occur with nasal reconstruction or in the unilateral cleft lip patient. In the case of nostril narrowing, a transposition flap using cheek tissue to widen the nasal sill is an excellent reconstructive option (Fig. 13). In cases in which there is stenosis of the nasal base secondary to trauma, excision of malignancies or iatrogenic injury, a composite graft works well. Combining auricular cartilage and skin, shaped in a triangle, can be placed in the floor of the nose to repair this deformity (Fig. 14)."

Figure 8. A, Planning of the V-Y advancement incision. B, The nasal tip has been augmented with a columellar strut and a shield graft, and the columella has been lengthened with the use of a V-Y advancement technique. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 9. Techniques for reducing the alar base and nasal sill. A, Excision of alar base for reduction of nasal flare. B, Direct excision of nostril floor to reduce the nasal sill. C, Combined reduction of alar base and nasal floor to reduce alar flare and nostril size. Note the more vertical orientation of the nostril. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 10. Alar cinch technique. A, Vertically oriented incisions completed within the nasal sill and horizontally oriented backcuts correspond with the amount of narrowing desired. B, Tissue to be cinched is de-epithelialized, and tissue overlying the anterior nasal spine is undermined. C and D, De-epithelialized tissue is cinched at the midline with a straight Keith needle. E, Vertically oriented nasal sill incision is closed. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 11. Alar base stitch. A, Excision of alar crease and nasal sill. B, Suture fixation with the use of a nasal base stitch. C, After, note that the nostrils are more vertically oriented and the alar base width is decreased. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 12. Correction of nostril asymmetry with the use of an inferiorly based transposition flap. A, Inferiorly pedicled tissue to be excised from lateral nasal wall. B, Tissue from nasal floor and vestibule is split. C, Pedicled flap is inset. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 13. Widening of the alar base and nasal vestibule with the use of cheek transposition flap. A, Excision of cheek tissue pedicled inferiorly. B, Medial rotation of cheek tissue into nasal vestibule and lateral advancement of ala. C, Inset of pedicled flap and recreation of alar crease. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

As is the case with the nasal base, nasal re-construction with the use of flaps may result in thickness of the anterior ala. A superior based alar margin transposition flap results in an increase in nostril size, thinning of the alar skin, and a more vertically oriented, triangular shaped nostril (Fig. 18).3

Medial Wall

Altering the structure of the medial wall primarily involves augmenting or manipulating the caudal end of the septum, medial crural feet, or the anterior nasal spine. Caudal end septal deformities can present themselves as major asymmetries in the nostril shape with associated nasal airway obstruction. Mild deformities of the caudal septum can be corrected easily by a septoplasty, whereas more severe caudal end deformities may require a closed

Figure 14. A, Stenosis of the nasal base with partial obstruction at the nasal vestibule secondary to a phenol burn injury. B, Stenosis and obstruction are corrected with the use of a composite skin and cartilage auricular graft.

Lateral Wall

Abnormalities of the lateral wall are related primarily to structural anomalies and deficiencies of the lateral crus or excess tissue of the ala. Unlike deformities of the nasal base, which are more often aesthetic, lateral wall abnormalities can result in significant functional deficits. In the case of alar collapse, the nostrils are vertically oriented and narrow. On inspiration, partial or complete obstruction of the external nasal valve may occur. Alar batten grafting using lower lateral replacement, augmentation, or transposition techniques allows for correction (Fig. 15). Bulky skin and large nostrils should be addressed by alar rim excision (Fig. 16). Careful attention to the location of the incision is critical to make certain that the closure will be placed as internally as possible. This will ensure that the scar is camouflaged within the shadows of the nose. The rim incision can be combined with alar base reduction excisions (Fig. 17). This is an excellent option when dealing with the ethnic nose that may have thick alar skin and alar flare.

Figure 15. A, Note the alar collapse with partial obstruction of external nasal valve. B, The alar collapse was corrected with batten grafts, resulting in improved nostril width and correction of nasal obstruction.

Figure 16. Alar rim excision. A, An ellipse of tissue is excised from the alar rim. B, Primary closure results in reduced alar flare and a more vertically oriented nostril. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 17. Alar base reduction in conjunction with lateral wall (rim) excision. A, An ellipse of tissue is removed from the alar rim in combination with an ellipse from the alar base. B. Primary closure results in a decrease in alar flare and alar base width. Works well with thick skinned individuals with increased nostril width. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Figure 18. Correction of nostril asymmetry with the use of a superiorly based rotation flap. A, Superior pedicled tissue to be excised from lateral nasal wall. B, Tissue from nasal vestibule and apex is split. C, Pedicled flap is inset and rim is closed. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

or open septorhinoplasty with transplantation of the caudal end and suture fixation of the septum to the medial crural feet and the prespinous fascia (Fig. 19).

As described earlier, the footplate segment of the medial crura is angled in two dimensions. Excessive lateral angulation of one or both of the medial feet can result in unsightly contouring of the columellar base (Figs. 20A-C). This type of contour deformity can be corrected as an office procedure or in conjunction with other rhinoplasty techniques by suture fixating the medial crural feet to one another, with or without subcutaneous fat excision (Fig. 20D). In addition, removal of excess anterior nasal spine bone or subcutaneous fat contributes to a smooth transition into the lobule.

There are many techniques that can be used to improve tip definition, change the tip projection, or narrow the nose. Dome division is an incisional technique initially described by Goldman.' The focus is on the domal segment of the middle crura and requires complete vertical division of the LLC. This maneuver results in increased tip definition and refinement. Because of the potential long-term problems with bossae formation, however, the authors recommend reconstituting the tip following dome division and trimming of excess LLC. The use of a columellar strut and tip graft are important tools in the armamentarium of the rhinoplastic surgeon. The primary goal is to provide adequate tip support, enhance tip refinement, and blend the tip into the contour of the nasal dorsum. An alternative to increase projection and enhance refinement is nasal tip

Figure 19. A, Caudal end deformity of nasal septum with partial airway obstruction. B, Resolution of nostril asymmetry and nasal obstruction following open technique septorhinoplasty with a caudal end septal transplant.

Figure 20. A, Foot segment of medial crura with variations in angles. B, High angulation contributes to a more horizontal nostril orientation. C, Straight configuration allows for a more vertical orientation of the nostril. D, Suture fixation of the medial crural feet, changing high angulation to straight. (By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Against this background, changes to the columellar are performed in an attempt to in-crease or decrease nasal tip projection. The columella can be viewed as the center pole of a tent. Addition or subtraction to the height of the center pole results in an increase or de-crease in projection. Changes in projection transmit changes to the nostril shape and orientation and create the illusion of changes in alar base width (Figs. 21 and 22).

SUMMARY

The nasal tip and resultant nostril shape have complex anatomical structure consisting of a cartilaginous framework and skin and soft tissue envelope. When preparing to perform rhinoplasty operations, it is important to consider ethnic and individual variations in the nasal tip, the nostril shape, and internal structure. By dividing the nasal tip into its respective subunits, the rhinoplastic surgeon can then formulate a systematic and pragmatic approach to the nasal base, lateral wall, and columella. Altering or augmenting one or all of these areas results in changes to the nasal tip and to the shape and orientation of the nostril.

Figure 21. A, Note the vertically oriented nostrils with an overprojected and wide amphorus nasal tip. B, After open septorhinoplasty with columellar strut, dome division, and a shield graft. Note, the decrease in nasal tip projection orients the nostrils more horizontally and creates the appearance of an increased alar base width.

Figure 22. A, Note the horizontally oriented nostrils, under-projected nasal tip, and wide alar base width. 8, After open septorhinoplasty with a cantilevered dorsal rib bone and cartilage graft and a columellar strut. The increase in nasal tip projection orients the nostrils more vertically and creates the appearance of a decreased alar base width.

REFERENCES

- Aufricht G: A few hints and surgical details in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 53:317-320, 1943

- Bardach J: Correction of nasal deformity associated with bilateral cleft lip. In Bardach J, Slayer KE (eds): Surgical Techniques in Cleft Lip and Palate. St. Louis , Mosby Year Book, 1991

- Burget GC, Menick J: Aesthetic reconstruction of the nose. St. Louis , Mosby Year Book, 1994

- Daniel RK: The nasal tip: Anatomy and aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg 89:216-224, 1992

- Daniel RK: The nasal base. In Regnault P (ed): Rhinoplasty: Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Boston , Little, Brown, 1993

- Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Deutsch CK: Objective assessment of standard nostril types: A morphometric study. Ann Plast Surg 11:381-389, 1983

- Goldman IB: The importance of the medial crura in nasal tip reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 65:143-147, 1957

- Huffman WC, Lierle DM: Studies on the pathologic anatomy of the unilateral hare-lip nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 4:225-234, 1949

- Joseph J: Nasenplastik and Sonstige Gesichtplastiken: Ein Atlas and Lehrbuch. Leipzig , Germany , Curt Kabitzsch, 1932

- Larrabee WF Jr, Makielski KH: Surgical anatomy of the face. New York , Raven Press, 1993

- Larrabee WF, Sherris DA: Principles of facial reconstruction. New York , Raven Press, 1995

- Gaylon McCollough E: General concepts. In Gaylon McCollough E (ed): Nasal Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia , WB Saunders, 1994

- Natvig P, Sether LA, Gingrass RP, et al: Anatomical details of the osseous-cartilaginous framework of the nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 48:528-532, 1971

- Nolst Trenite' GJ: Rhinoplasty: A practical guide to functional and aesthetic surgery of the nose. Nether-lands, Kugler Publications, 1993 and 1998

- Planas J, Planas J: Nostril and alar reshaping. Aesthet Plast Surg 17:139-150, 1993

- Sheen JH: Adjunctive techniques. In Sheen JH, Sheen AP (eds): Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. St. Louis , Mosby, 1987

- Sherris DA: Caudal and dorsal septal reconstruction: An algorithm for graft choices. Am J Rhinol 11:457-466, 1997

- Simons LR: Vertical dome division in rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 20:785-796, 1987

- Sykes JM, Senders C: Surgery of the cleft lip nasal deformity: Operative Techniques of Otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1:219-224, 1990

- Sykes JM, Senders CW, Wang TD, et al: Use of the open approach for repair of secondary cleft lip-nasal deformity. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1:111-126, 1993

- Weir A: On restoring a sunken nose without scarring the face. NY Med J 56:449-454, 1892