Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene Augmentation of the Lower Face

David A. Sherris, MD; Wayne F. Larrabee, Jr., MD

Most options for rejuvenation of the lower face use soft-tissue fillers that augment the appropriate sites. Each of these options has associated risks and benefits. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (E-PTFE) as a soft-tissue filler in the face.

From January 1991 through December 1993, the authors used E-PTFE soft-tissue patches for lower facial augmentation in 41 patients at 115 implant sites. Postsurgical follow-up has ranged from 2.5 to 4.5 years; during this time, complications have occurred in 4 patients. One implant had to be removed because of a seroma (1 patient), 4 implants required further secondary augmentation (2 patients), and 1 implant required revision because of malposition (1 patient). There have been no cases of implant infection, extrusion, long-term inflammation, or capsule formation.

In this article, the authors review the technical aspects of E-PTFE use and discuss issues relating to the long-term efficacy of this new option for soft-tissue augmentation. The technique is also compared with other options for rejuvenation of the lower face.

Deep creases in the melolabial region, perioral rhytids (wrinkles), and contour deformities or soft-tissue deficiencies of the lips are common aesthetic problems, especially in the aging face syndrome. Tradition-ally, the techniques used to treat these problems have depended on surface changes in the skin itself or on soft-tissue augmentation within or deep to the skin.'

Surface treatments, including dermabrasion and chemical peels, are quite successful in treating fine rhytids in the perioral region. However, they are insufficient for deep rhytids, deep melolabial creases, and labial hypoplasia.

Soft-tissue augmentation of the face has been accomplished with a variety of materials, including microdroplet silicone, bovine and human collagen, bioplastique, irradiated human dura mater, autogenous fat, dermal-fat grafts, and temporalis fascia.2-6 Unfortunately, all of these materials are associated with problems ranging from tissue antigenicity and rapid resorption to the need for a secondary surgical site for tissue harvest, and some have even been banned by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Furthermore, many patients fear the injection of biomaterials that could be associated with local antigenicity or systemic autoimmune disorders. Recently, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (E-PTFE) has been success-fully utilized in a variety of soft-tissue augmentation procedures of the face.1,7-12

E-PTFE has been used as a vascular grafting material since the early 1970s. This material is composed of nodules of solid polytetrafluoroethylene interconnected by thin, flexible fibrils of the same substance. This unique structure results in a microporous architecture (85% porosity) with a pore size of 10 to 30 um.8 The porosity allows tissue ingrowth and cellular attachment to promote anchorage, while the material it-self is highly biocompatible, with a minimal incidence of foreign-body reaction, rejection, or infection." Re-cent long-term animal studies13,14 have shown that the E-PTFE soft-tissue patch is a safe and reliable augmentation material with high biocompatibility, low tissue antigenicity, and increasing stability over time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 1991 through December 1993, we per-formed E-PTFE soft-tissue patch augmentation of the lower face in 41 patients. The results and outcomes of these procedures were retrospectively reviewed. The anatomic positions that were augmented included the upper and/or lower lips (21 patients, 63 implant sites), the melolabial folds (18 patients, 36 implant sites), the marionette lines (6 patients, 12 implant sites), the chin (2 patients, 2 implant sites), and the lower cheek (2 patients, 2 implant sites).

The 41 patients have been followed on a regular basis since surgery. At the second postoperative visit, within 4 weeks of surgery, the patients were asked if they had any complaints or if they had any loss of sensation, especially in the lip implant sites.

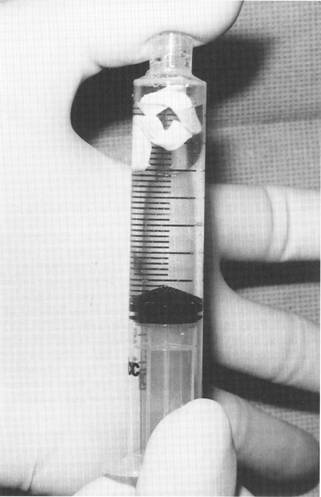

Fig. 1. Impregnation of the expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (EPTFE) patch with antibiotic solution.

The surgical technique we use requires a Cottle elevator, an alligator forceps, a No. 11 or No. 15 surgical blade, small tenotomy scissors, a toothed forceps, a needle driver, and suture material. Before surgery, the region to be augmented is marked with a surgical marker and then infiltrated with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. Patients are uniformly given perioperative cefazolin (Ancef, Kefzol) and postoperative cephalexin (Keflex, Biocef) for 5 days.

A scalpel is used to cut the implants from 2-mm-thick E-PTFE material. Care is taken not to stretch the implant during handling. The size of the implants is individualized for each patient. For augmentation of the melolabial folds, the implants typically measure 0.5 x 3.5 cm, with a slight tapering in width inferiorly. The implants for each side of the upper lip usually measure 0.3 x 2.8 cm and are rectangular in shape. Rectangular implants measuring about 0.3 x 6.0 cm are used for the lower lip, while triangular implants measuring approximately 0.8 x 1.0 X 1.3 cm are used for the marionette lines. Occasionally, the 2-mm-thick patch does not provide enough augmentation at the melolabial site. In such cases, two or more pieces are stacked and sutured together for greater height.

Prior to placement, the implants are vacuum impreg-Laryngoscopenated with kanamycin (1 g/40 mL normal saline). To accomplish this, the implants are placed in a 10-mL syringe, which is then filled with antibiotic solution. While the open end of the syringe is occluded with a finger, negative pressure is applied to the plunger (Fig. 1). Once the implants are impregnated enough to sink, they are immersed in the antibiotic solution until placement.

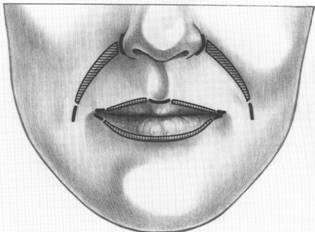

Fig. 2. Incision (heavy black lines) and E-PTFE patch placement (hatch marks).

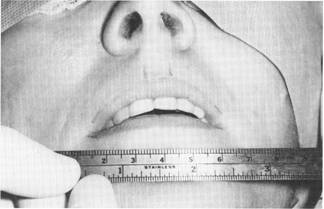

The incisions for augmentation of the melolabial crease are made at the superior and inferior ends of the crease (Fig. 2). The superior incision at the nasofacial groove is parallel to the nose, while the inferior incision is within and parallel to the melolabial crease. Incisions for augmentations of the lip and the marionette lines are made precisely at the vermilion border (Figs. 2 and 3).

Subcutaneous tunnels are then sharply and bluntly elevated through the incisions with one pass of the small tenotomy scissors. The tunnel in the melolabial region is made one third above the crease and two thirds below the crease. For flat lips, the tunnels are elevated precisely at the vermilion border for maximal plumping. For thin lips, the tunnels are elevated on the mucosal side adjacent to the vermilion border for maximal mucosal lip enhancement. The cupid's bow region is not routinely augmented, since it is important to retain this aesthetic curvature.

The triangular pockets for augmentations of the marionette lines are elevated in an inferior and lateral direction from the lateral lower-lip vermilion border. Each of the tunnels is further elevated, first with the sharp end of the Cottle elevator and then with the blunt end of the instrument (Fig. 4). A small corner of the lip lift is done during the placement of the marionette-line incision in cases where the augmentation appears insufficient to treat the problem.15

The alligator forceps is passed through the subcutaneous tunnels and used to grasp the appropriate implant (Fig. 5). With one end of the implant held by the alligator for-ceps and the other end held by the toothed forceps, the implant is slowly advanced into the subcutaneous tunnel with-out excessive stretching. A forceps can be used to place marionette-line implants directly into the subcutaneous pockets through the single incision.

Once the implant is in place, the skin is closed with skin sutures only (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3. Preoperative lip measurement. Note, also, the surgical marks indicating the incision sites with the intervening regions to be augmented.

Fig. 4. Cottle elevator used to widen subcutaneous pockets.

RESULTS

Typical results achieved with E-PTFE soft-tissue augmentation are shown in Figures 7 through 10. No wound complications occurred in our 41 patients. The only early complication was a seroma around an upper lip implant in one patient, necessitating removal of the implant. Late complications included a second procedure to increase augmentation of the melolabial folds in two patients (2 sites per patient), secondary to in-sufficient augmentation at the primary surgery, and a revision procedure to correct a minor contour abnormality at one melolabial implant site in one patient. Thus, the overall complication rate to date in our series is 9.8% (4/41), while the complication rate per implant site is 5.2% (6/115).

No clinically evident cases of E-PTFE soft-tissue implant extrusion, rejection, or sustained foreign-body reaction have occurred in our series. No cases of systemic autoimmune disorders secondary to E-PTFE implantation have been reported in the literature, and none have been seen in this series. All patients reported that their lip sensation remained normal.

Fig. 5. Alligator forceps used to place the implant.

The medial end of the incision for melolabialcrease augmentation may be made intranasally, but we have not used this approach because of concern about increasing the risk of implant infection. The external incision has not resulted in any scar problems.

DISCUSSION

Cosmetic augmentation of the lower face is a difficult problem that has been addressed in several ways. Probably the most common approaches are autogenous grafting (fat injection, dermal fat transplantation, or fascia transplantation) and bovine collagen injection. The advantages of the autogenous trans-plantation of materials include no risk of rejection, a decreased risk of infection, no use of an artificial product, and no problems, now or in the future, with FDA approval. The disadvantages of this approach include the unpredictable resorption of the graft (possibly necessitating future procedures), the need for a secondary harvest site and accompanying morbidity of the harvest (including pain, suturing, bone healing and possible adverse wound healing), and the difficulty in reversing a well-incorporated autogenous graft procedure if reversal should be required in the future.

Bovine collagen injection has a number of advantages. It is a relatively inexpensive, quick procedure that causes minimal postoperative pain or edema, carries little risk of infection, and is reversible (resorption of the material over weeks to months is anticipated).

Fig. 7. Patient 1. Left. Prior to lip augmentation. Right. One year after augmentation using E-PTFE patches.

Fig. 8. Patient 2. Left. Prior to lip augmentation. Right. Nine months after augmentation using E-PTFE patches.

The disadvantages of collagen injection include an allergic reaction to the injected material, the possible development of antibodies to the foreign collagen, and the need to repeat the procedure at intervals to maintain augmentation in the long term.

The technique of E-PTFE soft-tissue augmentation is a simple, reliable procedure that provides an alternative to the present techniques for lower facial augmentation. The advantages of E-PTFE augmentation include minimal tissue reactivity and ease of implant carving and shaping. There is also no need for a secondary operative side. No implant resorption occurs over the long term, and the implant can be re-moved easily. Thus, the procedure is potentially reversible, if so desired. The disadvantages of E-PTFE implantation in the sites discussed in this article include the risks of infection, seroma formation, implant extrusion, or foreign-body reaction that are associated with all alloplastic implants, the risk of implant placement in superficial sites that are subject to potential soft-tissue trauma, and the question of long-term capsular formation around the implants.

Some of the specific disadvantages of E-PTFE implantation of the lower face are addressed in our patients, who have been followed for 2.5 to 4.5 years. First, there have been no cases of implant infection, extrusion, or foreign-body reaction in our series. We encountered only one case of seroma formation. Thus, the rate of complications related to the material itself is exceedingly low and is at least comparable to the complication rate for autogenous transplantation to the lower face.

The additional augmentations required in two of our patients were necessary because an insufficient amount of material was implanted in the initial procedures. This kind of error is not attributable to the implant material and can just as easily occur with autogenous transplantation. In the patient who required revision of a contour abnormality, no fibrous capsule formation was found around the implant. In fact, the implant was removed, the pocket was explored and enlarged, and the implant was trimmed and returned to the pocket. The contour problem occurred secondary to a discrepancy between pocket size and implant size.

There is a potential risk of fibrous capsule formation over the long term, but the biocompatibility of E-PTFE appears to minimize this risk. In long-term animal studies,13,14 the finding of minimal histiocytic and foreign-body giant-cell reactions in the tissues surrounding E-PTFE implants supports the biocompatibility of this material. In each of these studies, only very delicate fibrous tissue surrounded the implants at 1 year. To date, no long-term studies of E-PTFE implantation have described significant fibrous capsule formation.

Finally, the risk of alloplastic implantation depends on both the material and the location of implantation. The location of implantation is important for two reasons: 1. the thickness and vascularity of the overlying tissue, and 2. the amount of movement at the site of implantation. The deeper the implant is buried and the smaller the implant is, the less the chance of extrusion, exposure, or infection. In the in our series, the implants were relatively small and were buried deep in the subcutaneous layer.

We do not advocate the intradermal placement of E-PTFE or the placement of large subcutaneous implants, especially in the lips. Linder12 presented a technique of E-PTFE lip augmentation using what we consider to be large implants in proportion to the depth of implant placement. Wolf16 recently described a patient with Gore-tex extrusion 8 days after massive lip augmentation. The photographs of this patient show massive undermining of the lip and mucosal sloughing due to the placement of large implants. This case report supports our hypothesis that only small implants should be placed in subcutaneous sites.

Some may argue that soft-tissue augmentation is not appropriate for the lips and perioral region due to their constant movement. There are several reason why we experienced no problems with such augmentation in our series. First, we used small implants and placed them subcutaneously, so movement does not cause underlying bone erosion or tissue erosion from rubbing across firm surfaces. Second, the E-PTFE material itself is slightly elastic and allows tissue in-growth to a mild degree. It may be that the implants become gently fixed to the soft tissue of the site and then stretch slightly during movement, rather than break free from soft-tissue attachments. This may also explain why no evidence of fibrous capsule formation has been found in this study or in other medium-length studies.

CONCLUSION

Questions remain about the long-term use of E-PTFE for soft-tissue augmentation. Will the implants cause fibrous capsules formation? Are the implants going to be easily removed in the very long term? Will the extrusion rate for appropriately sized implants remain exceedingly low? What sites and implant sizes are acceptable? How large an implant is acceptable? Until these and more questions are answered, E-PTFE should be used with care and with complete patient understanding of the risks and benefits of alloplastic implantation.

We could be faulted for our use of implants of in-sufficient size in some patients. However, until E-PTFE has been shown to be safe for subcutaneous implantation in the long term (10 or more years), we will continue to use small implants and to accept good improvement, rather than use large implants that improve the immediate result but may be more likely to extrude over time. The results of this study strongly support the safety and efficacy of E-PTFE augmentation of the lower face in the medium and long term.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Lassus C. Expanded PTFE in the treatment of facial wrinkles. Aesth Plast Surg. 1991;15:167-174.

- Shumrick KA, Kridel RWH. Comparison of injectable silicone versus collagen for soft tissue augmentation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14(suppl. 1):66-72.

- Elson ML. Soft tissue augmentation of periorbital fine lines and the orbital groove with Zyderm-I and fine gauge needles. JDermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:779-782.

- Ersek RA, Beisang AA. Bioplastique: a new textured copolymer microparticle promises permanence in soft-tissue augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(4):693-702.

- Nordstrom MR, Wang TD, Neel B. Dura mater for soft tissue augmentation evaluation in a rabbit model. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:208-214.

- Billings E, May JW. Historical review and present status of free fat autotransplantation in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:368-381.

- Conrad K, Reifen E. Gore-tex implant as tissue filler in cheek lip groove rejuvenation. J Otolaryngol. 1992;21:218-222.

- Konior RJ. Facial paralysis reconstruction with Gore-tex soft tissue patch. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118: 1188-1194.

- Cisneros JL, Singla R. Intradermal augmentation with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-tex) for facial lines and wrinkles. JDermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19;539-542.

- Petroff MA, Goode RL, Levet Y. Gore-Tex® implants: applications in facial paralysis rehabilitation and soft-tissue augmentation. LARYNGOSCOPE. 1992;102:1185-1189.

- Waldman SR. Gore-tex for augmentation of the nasal dorsum: a preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;26:520.

- Linder RM. Permanent lip augmentation employing polytetrafluoroethylene grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:1083-1090.

- Neel HB. Implants of Gore-tex: comparison with Teflon-coated polytetrafluoroethylene carbon and porous polyethylene implants. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;109:427-433.

- Maas CS, Gnepp DR, Bumpous J. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-tex soft-tissue patch) in facial augmentation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1008-1014.

- Austin HW, Weston GW. Rejuvenation of the aging mouth. Clin Plast Surg. 1992;19:511-524.

- Wolf DL. Complication following lip augmentation with Goretex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:1334-1335.